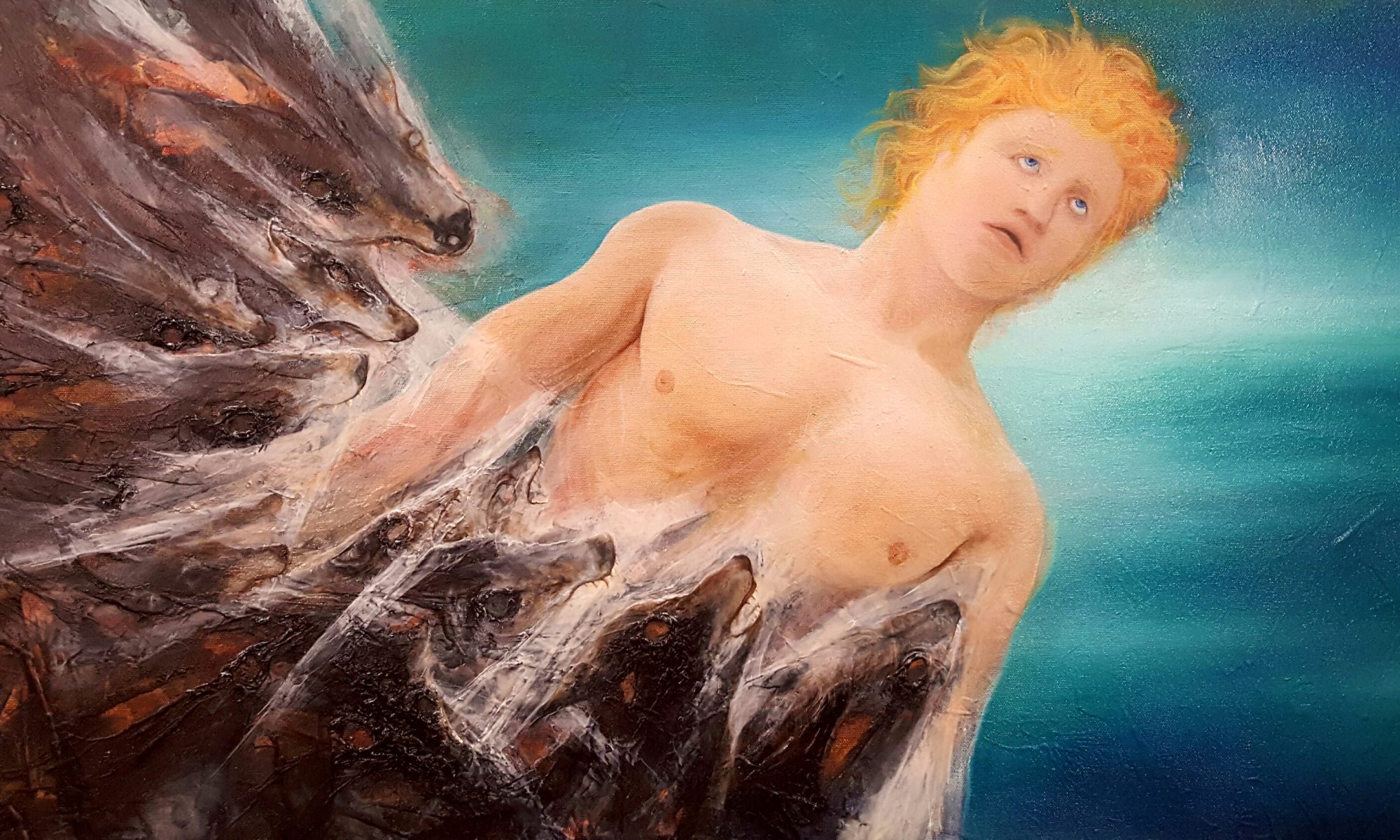

One of the most neglected topics in discussions of the artistic process is the internal state of the artist, and how it can either facilitate or obstruct the act of creation. The successful invocation and use of states of intense concentration and passionate release are tools that can be as critical to the artist as brushes or pallet knives. Even when such aspects are considered, the focus is most often relegated to highly refined states of productive focus. Far less frequently discussed, and perhaps less frequently invoked, are the states of disorder, dissociation, and frenzy.

Ultimately, the tempests of the unconscious mind are the source of the well-spring of creativity, and in the realm of the spirits there are muses aplenty eager to speak to the attentive listener, or else howl in discordant fury. While the hidden interplay between feeling, symbol, and desire is, by definition, difficult to consciously navigate, it contains the keys to unlocking fire in its depths.

One of the clearest representations of this source is found in the Greek god Dionysus. Often miscast as the ‘god of wine’, this portrayal mistakes the method for the source. A far more revealing descriptor of his essential character would be ‘god of intoxication.’ Considered dangerous and subversive to the social order, before its brutal repression by the Roman state cultic worship of Dionysus centered on the embrace of states of altered consciousness through intoxicants, forbidden sexual practices, and omphagic frenzy. Despite the diversity of these rituals, they shared a common purpose as a bridge to states of ritual madness.

While sparagmos is possible as well, for the artist such states of divine ecstasy may instead manifest themselves as a surrender to the pure expression of creative energy. While application of this passion often takes the form of wild extremes of expressiveness, it can also result in sparsely proficient application of familiar techniques in subtly radical ways. This should come as no surprise when one considers that the physical skills governing artistic practice are almost always most effectively subconsciously learned and applied. It must also be cautioned though that the creative potential inherent in these unstructured states is balanced by the danger of a work being overtaken by its chaos.

When this chaos emerges in a greater context however it can fulfill a direct aesthetic necessity. Even in works whose emphasis is harmony, the contrast provided by discord may elevate a work to new heights. The Nietzschean aesthetic framework for instance considers that for an artistic endeavor to reach its highest potential it must embrace both the frenzied passion of Dionysus, as well as the subtle harmony associated with the god of light and beauty: Apollo. Indeed, just as imperfection is a necessary component of the perfect phenomenon, it is ultimately the fusion of states that permits the greatest realizations of beauty.

For a culture that consistently emphasizes the rational and orderly at the cost of the intuitive, often to the point of suffocation, utilizing the disordered madness of Dionysus can seem foreign and uncomfortable. However, the use of ecstatic states has by no means been a limited experiment. Examples of similar practices are familiar enough that their absence appears as the aberration, rather than than the norm. Sufi mystical dancers and poets, accounts of viking-age berserkers, indigenous shamanic ceremonies, and Buddhist Tantric practice; all share similar of states of intoxicated passion. Indeed, even the earliest known human story is suffused with the motifs of ecstatic ritual; as Gilgamesh attempts a resurrection he does so with shamanic drumming and a ritual invocation to the spirits.

Regardless of whether the artist chooses to directly commune with the spirits of Dionysus, the dynamic life of the discordant can not be ignored. Even as a subset of the creative act, all outpourings of feeling originate in the movings of the psychic depths, and creative endeavours that lack feeling fail the most basic task of art. In the creative deserts of rationality, it is the leviathans of our own abysses that offer us water.

To see more of Noah’s work, visit NAStein.com